Specific relative angular momentum

In celestial mechanics, the specific relative angular momentum (h) of two orbiting bodies is the vector product of the relative position and the relative velocity. Equivalently, it is the total angular momentum divided by the reduced mass. Specific relative angular momentum plays a pivotal role in the analysis of the two-body problem.

Definition

Specific relative angular momentum, represented by the symbol  , is defined as the cross product of the relative position vector

, is defined as the cross product of the relative position vector  and the relative velocity vector

and the relative velocity vector  .

.

where:

is the relative orbital position vector

is the relative orbital position vector

is the relative orbital velocity vector

is the relative orbital velocity vector

is the total angular momentum of the system (i.e. the sum of the angular momenta of each body)

is the total angular momentum of the system (i.e. the sum of the angular momenta of each body) is the reduced mass

is the reduced mass

The units of  are m2s−1.

are m2s−1.

The  vector is always perpendicular to the instantaneous osculating orbital plane, which coincides with the instantaneous perturbed orbit. It would not necessarily be perpendicular to an average plane which accounted for many years of perturbations.

vector is always perpendicular to the instantaneous osculating orbital plane, which coincides with the instantaneous perturbed orbit. It would not necessarily be perpendicular to an average plane which accounted for many years of perturbations.

Angular momentum

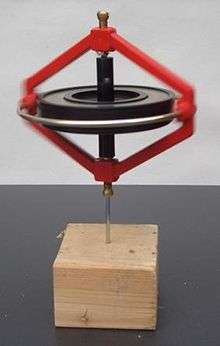

In physics, angular momentum (less often moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is a physical quantity corresponding to the amount of rotational motion of an object, taking into account how fast a distribution of mass rotates about some axis. It is the rotational analog of linear momentum. For example, a conker twirling around on a short chord has a lower angular momentum compared to twirling a large heavy sledgehammer at high speed. For a conker of a given mass, increasing the length of chord and angular speed of twirling increases the angular momentum of the conker, and for a fixed angular speed and length, a heavier conker has a larger angular momentum than the lighter conker. In principle, the conker and sledgehammer could have the same angular momentum, despite the differences in their masses and sizes.

Symbolically, angular momentum it is denoted L, J, or S, each used in different contexts. The definition of angular momentum for a point particle is a pseudovector, L = r×p, the cross product of the particle's position vector r (relative to some origin) and its momentum vector p = mv. This definition can be applied to each point in continua like solids or fluids, or physical fields. Unlike momentum, angular momentum does depend on where the origin is chosen, since the particle's position is measured from it. The angular momentum of an object can also be connected to the angular velocity ω of the object (how fast it rotates about an axis) via the moment of inertia I (which depends on the shape and distribution of mass about the axis of rotation). However, while ω always points in the direction of the rotation axis, the angular momentum L may point in a different direction depending on how the mass is distributed.

Angular momentum operator

In quantum mechanics, the angular momentum operator is one of several related operators analogous to classical angular momentum. The angular momentum operator plays a central role in the theory of atomic physics and other quantum problems involving rotational symmetry. In both classical and quantum mechanical systems, angular momentum (together with linear momentum and energy) is one of the three fundamental properties of motion.

There are several angular momentum operators: total angular momentum (usually denoted J), orbital angular momentum (usually denoted L), and spin angular momentum (spin for short, usually denoted S). The term "angular momentum operator" can (confusingly) refer to either the total or the orbital angular momentum. Total angular momentum is always conserved, see Noether's theorem.

Spin, orbital, and total angular momentum

The classical definition of angular momentum is  . This can be carried over to quantum mechanics, by reinterpreting r as the quantum position operator and p as the quantum momentum operator. L is then an operator, specifically called the orbital angular momentum operator. Specifically, L is a vector operator, meaning

. This can be carried over to quantum mechanics, by reinterpreting r as the quantum position operator and p as the quantum momentum operator. L is then an operator, specifically called the orbital angular momentum operator. Specifically, L is a vector operator, meaning  , where Lx, Ly, Lz are three different operators.

, where Lx, Ly, Lz are three different operators.

Relative angular momentum

In celestial mechanics, the relative angular momentum ( ) of an orbiting body (

) of an orbiting body ( ) relative to a central body (

) relative to a central body ( ) is the moment of (

) is the moment of ( )'s relative linear momentum:

)'s relative linear momentum:

where:

is the orbital position vector of the orbiting body relative to the central body,

is the orbital position vector of the orbiting body relative to the central body, is the orbital velocity vector of the orbiting body relative to the central body,

is the orbital velocity vector of the orbiting body relative to the central body, is mass of the orbiting body.

is mass of the orbiting body.For a body in an unperturbed orbit about a central body, the orbital plane is stationary, and the relative angular momentum ( ) is perpendicular to the orbital plane.

) is perpendicular to the orbital plane.

For perturbed orbits where the orbital plane is in motion, the relative angular momentum vector is perpendicular to the (osculating) orbital plane at only two points in the orbit.

Uses

In astrodynamics relative angular momentum is usually used to derive specific relative angular momentum ( ):

):

where:

is mass of the orbiting body.

is mass of the orbiting body.See also

References

Podcasts: